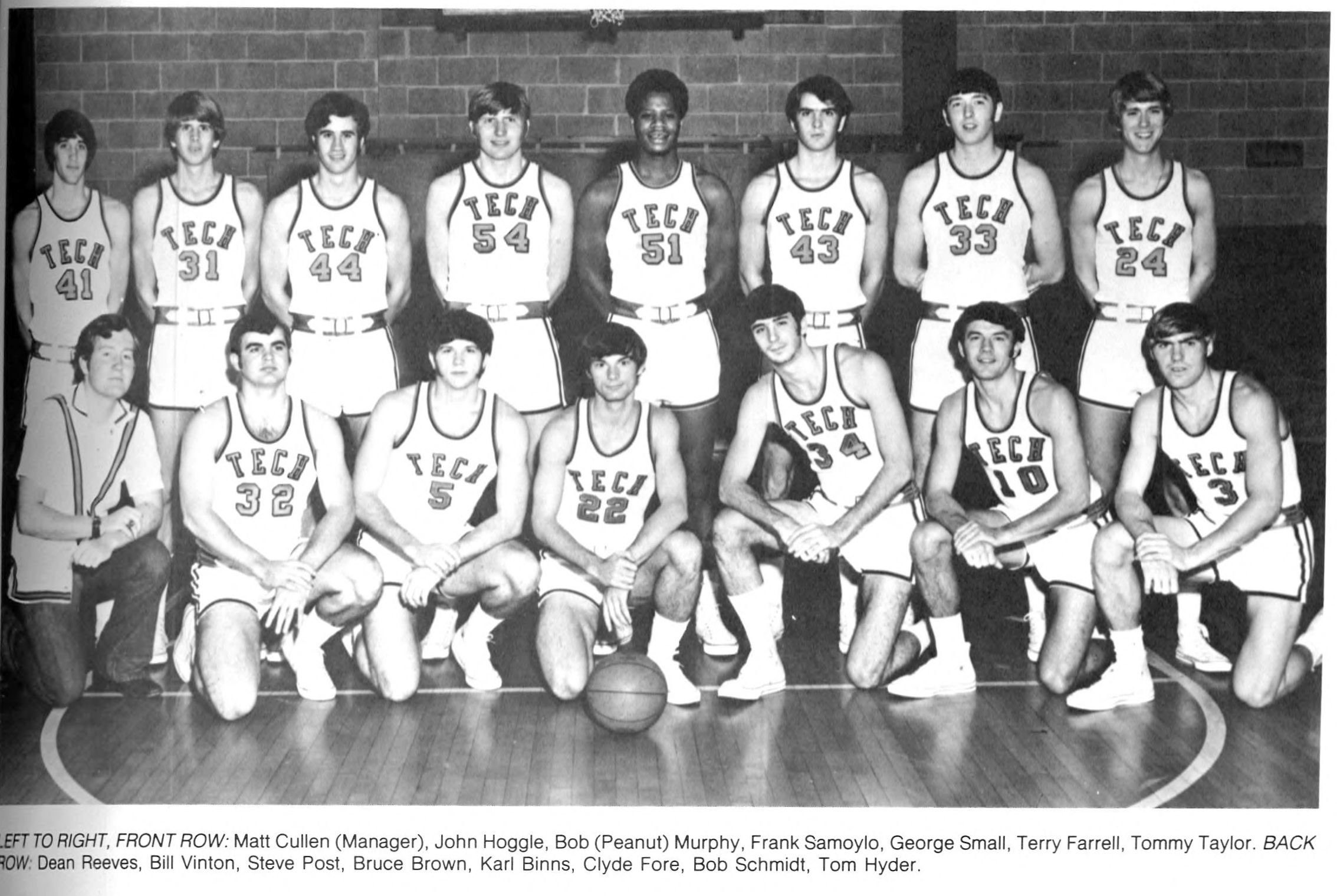

This story originally appeared on February 13, 2018, coinciding with Binns’ visit to campus more than 45 years after he became the Yellow Jackets’ first African-American varsity basketball player.

By Matt Winkeljohn | The Good Word

Karl Binns returned to The Flats the other day, nearly half a century after becoming the first African-American scholarship basketball player at Georgia Tech, and so, so much had changed.

Beyond the fact that two-thirds of the Yellow Jackets’ 12 scholarship players are minorities, and roughly half of Tech’s coaching and support staffs are comprised of African-Americans, just about everything else is different at his hometown school “except the ceiling” in McCamish Pavilion.

Although he spent just one season playing for Tech, in 1971-72, and it wasn’t entirely pleasant as the Jackets went 6-20 one year after finishing runner-up in the NIT, Binns has from afar developed greater appreciation for the Institute.

“One of my biggest regrets is not finishing here,” Binns said after touring the Zelnak Practice Facility, Tech’s locker room and McCamish with director of player personnel Mario West. “I’m happy with what happened, but I now do appreciate the brand, and I understand that Tech can open up doors for you.”

In a way, Georgia Tech long ago opened Binns’ eyes and helped him turn to a pursuit of academics for the better part of a lifetime.

While growing up on the West Side of Atlanta, he was a solid but not spectacular player at long-gone St. Joseph’s Catholic High School in downtown Atlanta, a relatively lean, 6-foot-5 rebounder. He needed work on his basketball and academic games.

So, he went to Truett-McConnell Junior College for two years in Cleveland, Ga., where he and Barry Allen were the first African-American basketball players in school history.

“My game wasn’t really there,” he recalled of the transition. “I didn’t get any offers coming out of high school.”

That first season at Truett-McConnell, which is now a four-year institution that competes in NAIA athletics, “was tough,” he said. “You’re a black Catholic at a Baptist school in north Georgia … I was there to do something for the school.”

Assistant coach Gerald Cox became head coach before Binns’ second season, Truett-McConnell won more than it lost, he grew a couple inches and averaged about 15 points and 16.7 rebounds per game to lead the old Georgia Junior College Athletic Association.

That is a better memory.

“It was a winning season. Everybody loves a winner,” Binns said. “We had an opportunity to bring some energy back to campus. I can find a commonality with anybody. In the dorms after meals, we used to put a TV out and sit around and watch Hee Haw.

“St. Joe’s prepared me well. It’s was a good learning experience. I got grounded, and then Tech came calling.”

Binns visited the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, and figured to next be a Moccasin – until former Georgia Tech coach Whack Hyder showed up.

The Jackets were 23-9 in 1970-71, but 6-10 center Rich Yunkus, the leading scorer in school history, and fellow seniors Jim Thorne, Howard Thompson and Tommy Wilson graduated from that team.

“My coach gets a call and says the coaches from Georgia Tech are going to come up and see you,” Binns said. “My coach was trying to encourage his alma mater, Appalachian State. The recruiting process … you don’t have the mentorship or guidance there.

“I discussed it with my family. The lure was [Tech] and [Division I], the big leagues, and they were a major college independent. We’ll probably never know if they were under pressure to go get an African-American. They probably just had to get somebody who could do something inside and get some rebounds.”

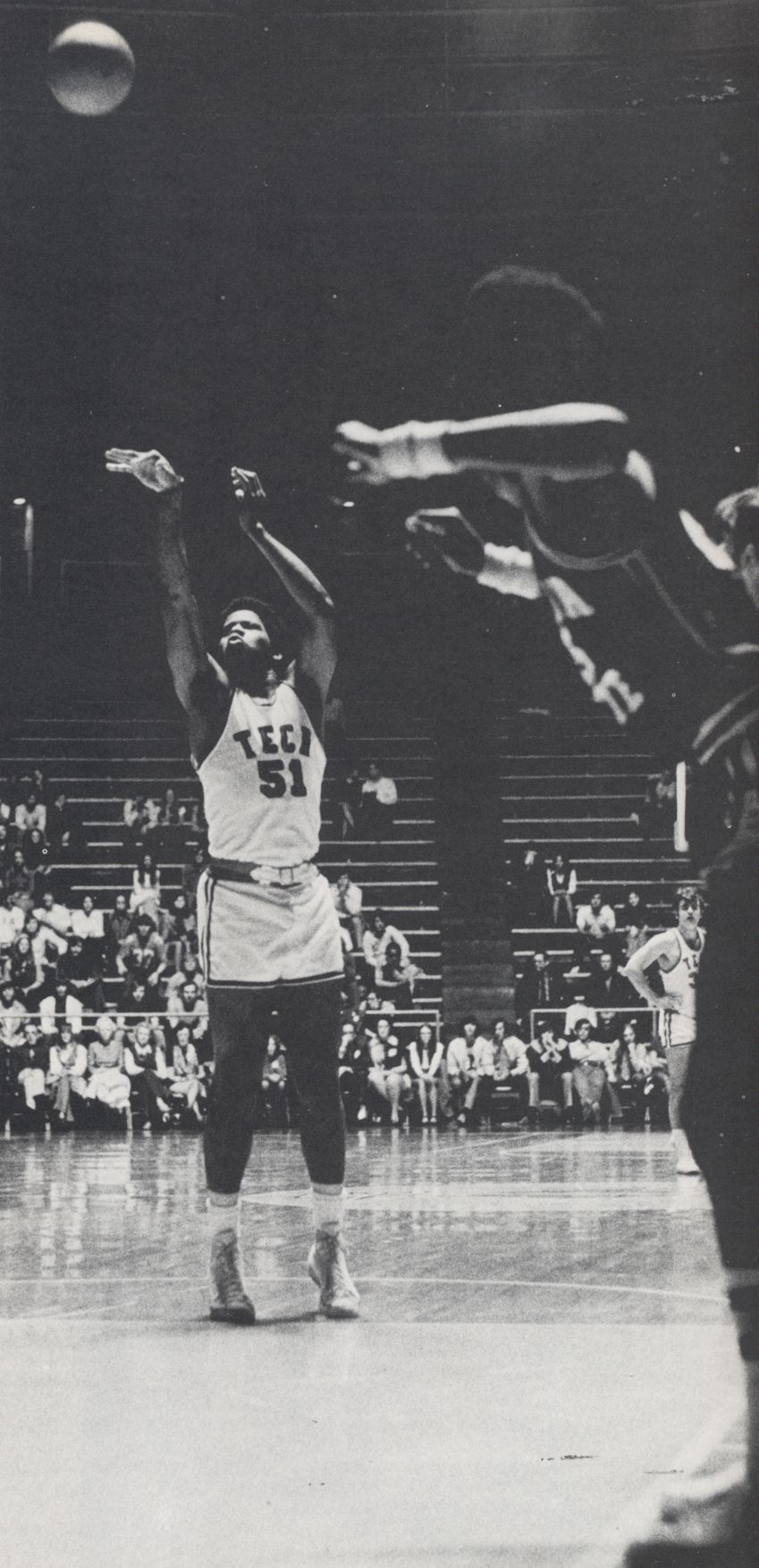

Binns was 6-7 by this time, and he got rebounds – he grabbed 6.5 per game to lead the team while scoring 8.8 points – but he didn’t get school. The former management major said, “there were so many distractions.”

He can’t help but wonder if he wasn’t accepted to a fraternity for sake of his race, but said while visiting Tech on Feb. 9 and then attending the Duke game two days later, “I didn’t really experience any overt racism other than somebody invited me to go to one of their fraternity things . . . It wasn’t rocky here.

“When you have a losing season, you find commonalities to have fun. After the season, my teammates came over to my parents’ house. We had a party. It wasn’t a dialogue with conversations about race.”

Academics have long been a primary topic of conversation among the Binns. Three of his four children have college degrees, and his youngest daughter will graduate from Spelman in May. One of his two sons works at Maryland-Eastern Shore as a recruiter.

But after that one season at Tech, Karl had to get his academic act together “if I was going to stay in the family.”

So, he transferred to Morris Brown, which was even closer than Tech to his family’s home on the West Side. There, he stepped away from basketball for a year because, “I had to get my academics back on track,” and then played one more season of college ball while earning a degree in management.

After two professional seasons with a German team, Binns returned to Atlanta and went into the work force. Soon, his company transferred him to Baltimore.

Married and building a family, he earned an MBA at Morgan State, tried law school for a year at Mercer University in Macon, taught for a while at Morris Brown and Bethune-Cookman, and then moved to Maryland-Eastern Shore, where he earned a Ph.D. in organizational management.

Clearly, Binns came to get school.

He’s an assistant professor and lecturer in Maryland-Eastern Shore’s Department of Hospitality and Management within the School of Business and Technology.

Tommy Taylor, Binns’ former Georgia Tech teammate, has long encouraged him to return to campus.

Finally, Binns came back.

He visits Atlanta every other month or so, tending to his elderly mother who still lives in the same house on the West Side. He has extensive family here, including two of his four children.

Sometimes, though, he feels lost in Atlanta. So much has changed. The city’s population is six or seven times what it was when he last lived here, and the roads are ever chocked full of traffic.

Plus, Alexander Memorial Coliseum is gone, but for the skeleton of the ceiling. A slew of buildings on campus are new to him.

Still, after touring the facilities, meeting head coach Josh Pastner on the court in McCamish, and even tossing in a right-handed hook shot, Binns is wistful. He’s seems quite pleased to learn that the academic support system has grown within the Georgia Tech Athletic Association, yet he has a question.

“It made me bitter in some ways. It was a sense of failure in a lot of ways,” he said. “Every time I come home I get lost. Thank goodness for whoever invented GPS.

“At first, I was reluctant about doing this, but I’m really glad I did because it’s helped me appreciate what’s here.”