This story originally appeared in the Spring edition of Everyday Champions magazine. You can read the entire issue and access archived editions here.

By Matt Winkeljohn

For quite a while, James Banks III couldn’t keep pace with his mother, who became quite a runner, and neither could his older sister, Marissa. Even the family dogs struggled to stay with Mom when she went running on the pathway from Stone Mountain toward Atlanta.

James was in elementary school then.

Now, Mom can’t walk, and it’s hard to keep up with James as he drives toward the finish of his college basketball days at Georgia Tech, with the goal of playing in the NBA.

Tracking his hoops story isn’t so easy either.

He’s been centering the Yellow Jackets for two seasons, after languishing on the bench for two at Texas, and you’ll be hard pressed to keep in order the four high schools where he grew from a very tall neophyte with minimal basketball experience to a force.

There’s a lot to process with Banks, and it starts with Sonja Banks prohibiting him from playing basketball when he was a kid. James says, “Mom over-protected me as a kid,” and Sonja, who is now a paraplegic, “will tell you that’s no lie.”

James Jr., his Dad, died in a motorcycle accident on North Avenue, behind what is now Ponce City Market. The big little guy (James is a solid 6-feet-10 now, with a standing reach of almost 9-feet-4 toward the goal) was four.

James III didn’t get to play, “because I didn’t want him to go down the wrong path,” Sonja admits. “I ran five miles a day, and I was coming back, and I passed the park (where kids played). I thought I smelled marijuana. I was really strict on him. I kept him up under me, and sometimes when I look back, I wish I did things a little differently. I should have known by his size that basketball was his sport.

“(By then) being a single mom, after something so tragic, I think things would have been different if his dad was around, and he would have been exposed to more sports.”

A few years after the death of James, Jr., Mom relented one day when the family was at Stonecrest Mall, and youth league officials had a sign-up table there. “Because his dad had played football, I think he wanted to play football for the DC Trojans,” Sonja says.

James Jr. – Dad — played football at North Carolina Central. He was 6-7, and he may have even played a little bit of ball in an obscure semi-pro league.

Sonja played a little basketball at Towers High in DeKalb County. She was 6-feet before the accident on Feb. 25, 2015, that broke her back. “I only made the team because I was tall,” she says.

James III eventually took off in basketball in part because he is also tall. He sure wasn’t good when he made the JV squad at Columbia High in Decatur as a freshman. He’d been 6-3 in middle school and kept growing. Then, his mother let him try out for a new sport. He did almost nothing.

At the time, he figured he had a shot as a defensive end, or as an offensive lineman, maybe as a tight end, but basketball looked so cool. So, he swayed his mother into letting him play.

“Moving bodies, that’s really what I thought my thing was going to be, and I just remember I wanted to play (basketball) so bad. I didn’t make the varsity, and just doing the three-man weave was so hard for me, so challenging,” he says. “They wouldn’t even let me touch a ball.”

But the big boy got better fast.

He transferred to St. Francis School, in Alpharetta, for his sophomore year and played off the bench for a state championship team that included Malik Beasley, who now plays in the NBA for the Timberwolves. Other teammates included Kaiser Gates, who went on to play for the University of Arizona, and the NBA’s Grizzlies, Cavs and Hornets. They were both one-and-done players in college. Another teammate, Kobi Simmons, was on the team as well. He played at Xavier for three years, and is working now in the NBA’s developmental G-League.

Then, Banks played some AAU ball.

“That summer I played for the first time with Stampede, made a little bit of noise and got my feet wet,” he says. “Playing at St. Francis with all those guys, we had college coaches all the time. It opened up a new lens on what basketball could be for me.”

St. Francis head coach Cabral Huff took a job at Georgia Southern, and Banks soon transferred away to Mt. Vernon Presbyterian in Sandy Springs for his junior season. And he rocked more.

In the middle of that season, his mother went skidding off of I-20 while driving to ministry duties outside of Anniston, Ala.

Mostly, she lives on the Move of God Bible Way Tabernacle property outside of Anniston, tended to by church members. When in Atlanta, which is a few days a month – chiefly when James has a basketball game – she stays with her mother in Decatur. Head pastor Prezzel Lane usually drives her back and forth to and from Atlanta.

James thought she was going to get better, and went to play his senior season on scholarship for La Lumiere School in La Porte, Ind. That’s a hugely successful prep program.

And then he chose Texas without knowing that fellow center Jarrett Allen would join the Longhorns a couple months later, just after James showed up on campus. Banks didn’t play much that season, and Allen was drafted after just one year of college by the NBA’s Nets at No. 22.

A season later, center Mo Bamba showed up at Texas, and the freshman was in 2018 drafted No. 6 by the Magic. Again, Banks played little in what was his sophomore season.

The timeline in the head of Banks III wasn’t unfolding. “As a 16 or 17-year old, I didn’t think I was going to be in college more than two years,” he said.

Mom wasn’t getting better as fast as everyone had hoped, and the combination of James’ athletic and life realities led him back to Atlanta. So, he put his name in the transfer portal.

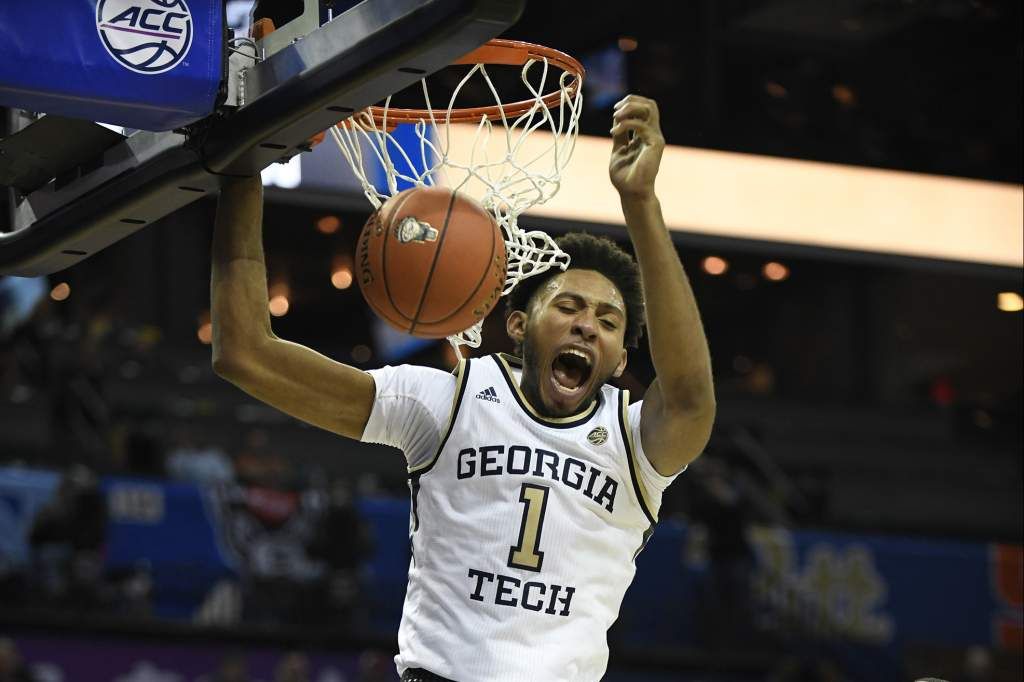

Now, he majors in history, technology and society at Tech, and is among the ACC’s best shot blockers, quite a rebounder, and in line to score about a dozen points per game.

“I think James has progressed in a lot of fundamental areas that may not jump out at somebody,” says assistant coach Eric Reveno, who works chiefly with Tech’s big players. “His technique on things, his shot blocking, his rebounding, some of the athletic plays he makes have always just naturally been there.

“But the fundamental skill base of being a post player, a basketball player, wasn’t fully developed, so we’ve gone back and shored things up. It’s sealing, and positioning and angles.”

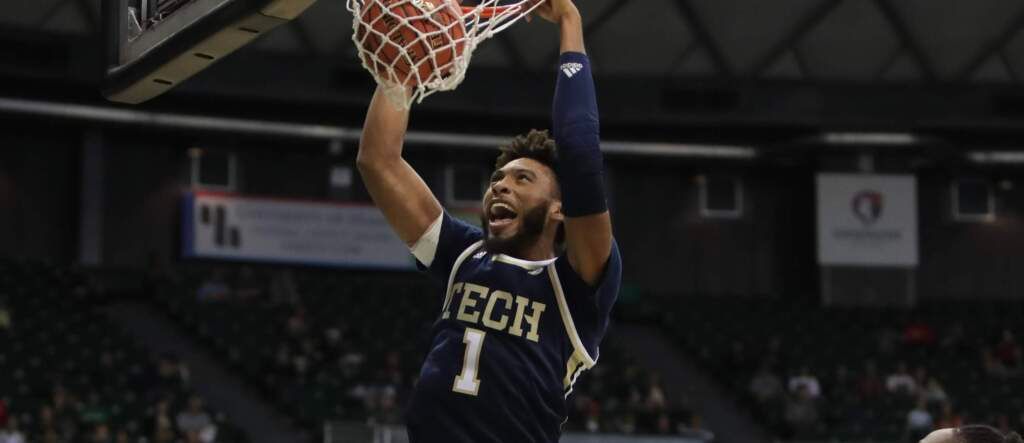

James Banks III in Action

Banks is always shoring up, and sometimes it costs him.

He’s not laser-focused all the time.

Maybe that’s because he cares so much about so many.

First thing every day, “I call my mom and we pray,” he says. “We talk at least three or four times a day, or text some.”

Banks is well spoken, like his mother, and he’s just as likely to come upon a media interview with teammates or head coach Josh Pastner and pop up two fingers behind the head of whomever is on camera as he is to show up with one of his multiple pairs of Crocs on his feet.

Or, he might just stop to talk.

Banks is different from his predecessor, Ben Lammers, who played out of the high block. James plays mostly low, but is so often so high on life. Reveno describes both as highly intelligent, Lammers as an introvert and Banks as an extrovert.

“I wouldn’t say he’s happy-go-lucky just because he’s wearing bright Crocs and two different color socks. He enjoys himself; he enjoys people;” Reveno says. “We go to a restaurant and the guys are polite and say hello, but James talks and meets some people, talks to servers. We leave and people say, ‘Your guys are so friendly,’ and that’s the James Banks effect.

That more than basketball, or football, James Banks III is big.

“I believe can hold my own with anybody on this Earth on the basketball court. I believe my best basketball is ahead of me.”

And, no longer in front, Sonja James from her wheelchair knows there will be more to life than hoops for her baby.

“Every parent wants their kid to fulfill their dream, and what I’ve learned in life with him if you give a person just a little bit of fame or notoriety, you’ll find out what that person is really like,” Sonja says. “What I’ve come to learn is that James will not sway from what I’ve taught him. What I’ve always taught him is to always be respectful, show love to those in despair. I don’t want him to ever, ever look down on people. What I’ve found is that if there’s one kid that’s over there by himself, go over there to see what you can do.”

In many ways, James III is fulfilling his dream on a daily basis, and his basketball journey is just beginning.