Basketball coach Ben Jobe spent one season on The Flats, but he left a lasting mark

By Matt Winkeljohn | The Good Word

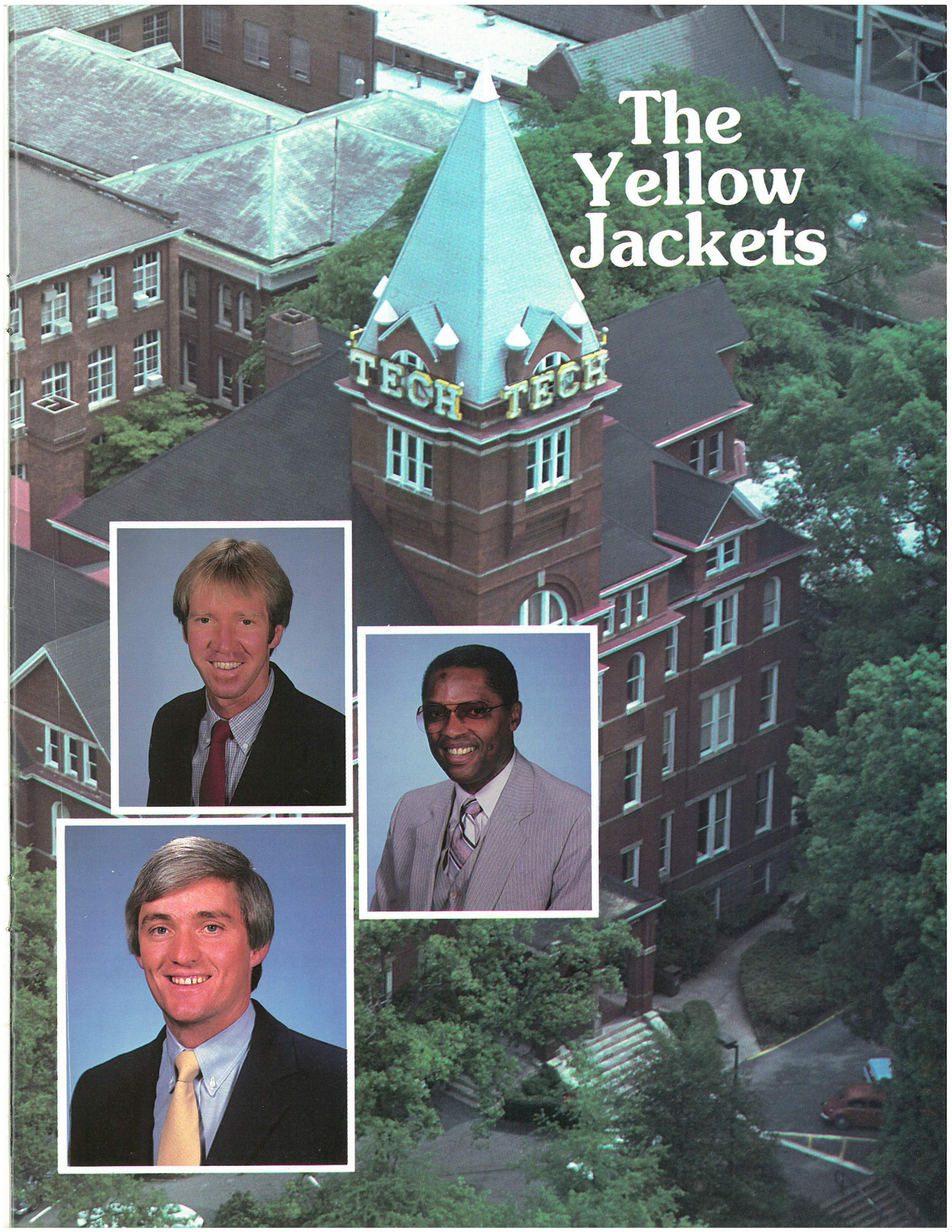

Before he left a couple years ago, Ben Jobe had a habit of doing things quickly, like when Georgia Tech’s first African-American assistant basketball coach spent just a year on The Flats.

The wise man from Nashville was an outlier in is lone season on Bobby Cremins’ first coaching staff, in 1981-82. He was the philosopher among hyperactive New Yorkers, and yet he hung around the game he loved long enough to become the only member of that office to have a national honor as a namesake.

The Ben Jobe Award is annually bestowed upon the most outstanding minority head coach among NCAA Division I basketball teams. That’s fair, given that as a head coach – mostly at Historically Black Colleges and Universities – his teams won 524 games. That happened before he passed away in March of 2017 at age 84 after a battle with lung cancer.

This man could be as patient as his surname suggests. Supremely well-read, he saw more than most, and told great stories touching many topics, rancorous race relations included. But rarely was he still for long. Off the court, Jobe was restless, and on the court, he loved fast-break hoops — which his Southern University squads used to great effect, as when the Jaguars ran ACC Tournament-champion Tech out of the 1993 NCAA Tournament.

Oh, and Cremins – who was at McCamish Pavilion when Jobe was honored on Feb. 16 while the Jackets hosted No. 17 Florida State – said Jobe, “probably should have been the new head coach,” back in 1981. But, “it wasn’t popular to hire a black coach.”

True enough. When athletics director Homer Rice went looking for a new basketball coach in 1981, no black man had yet been tabbed to run a major program in the South. That would first happen when Arkansas hired Nolan Richardson in 1985.

Rice chose Cremins, a wired, bouncy lad who’d done good things in his first job at Appalachian State University after playing for and coaching with the legendary Frank McGuire, another New Yorker, at South Carolina.

Soon after moving to Tech, Cremins hired George Felton, yet another from the Big Apple, who like Bobby before him was a player and graduate assistant at South Carolina. There, they all intersected when Cremins and Jobe served on McGuire’s staff as Felton played.

Before long, while looking for players and another assistant, Cremins and Felton were “were driving somewhere in Atlanta and I said, ‘What about Ben Jobe?’” Felton recalled. “Bobby said, ‘That’s a great name.’ I told Bobby, ‘He’ll keep you balanced.’”

Yeah, growing up poor in an enormous family in Nashville, Jobe would play different cards than did Cremins, Felton and even McGuire. He was a counter weight of sorts, although he favored nothing slow.

In that year at Tech, Jobe pushed and pontificated.

He wanted to the Jackets to pick up the pace, as his teams did when he was in charge at HBCUs Talladega, Alabama State and South Carolina State prior to working for McGuire as an assistant. But Brook Steppe was a shooter, and he and fellow starters Maurice Bradford, Lee Goza, Brian Howard and George Thomas were not fleet of feet in 1981-82.

“We couldn’t run the way he wanted us to run. I had loved fast break basketball, but he took it to another level,” Cremins said. “Very polished. He could get in a conversation with anybody about any subject. He would talk to us about the old days and the racial challenges.”

Jobe slowed down enough in his time at Tech to confirm a point guard whom Felton found and recruited like mad.

“I had one Friday night in the early summer when Bobby first got the job, and I said I’m going down to Jacksonville for a big AAU tournament,” Felton said. “They had the AAU team from Enid, Okla., and they had Mark Price. I called Bobby, and told him he’s fantastic. I made like 12 trips out there.”

Cremins went a little crazy about his young assistant’s forays to Oklahoma.

Felton recalls Cremins in a staff meeting yelping, “He’s going to spend the whole [recruiting] budget, and we don’t even know if the kid can play.”

So, the head coach sent Jobe to Oklahoma to watch Price in a high school game, to back-check him.

Then, there was a meeting.

“I was a little nervous because Ben was coming into the office. And Ben said, ‘I don’t know what we’re doing there,” Felton said. “Bobby starts [ranting], ‘See, I told you, [Felton] doesn’t know what he’s doing. He’s running around like a chicken with his head cut off.’

“Ben let Bobby finish, and he said, ‘What I meant was I don’t know why UCLA and North Carolina and all those big schools are not there.’ Bobby said, ‘Well, I gotta get out there.’”

Price signed in 1982 with Tech, as did John Salley. Their jerseys are in the rafters.

(story continues below)

Jobe sprang from the game’s genesis. The teenaged gym rat tracked former Tennessee A&I (now Tennessee State) head coach John McLendon in the 1950s, bumping around Nashville’s local YMCAs, basketball tournaments, clinics and camps.

The late McLendon, whose feats can be found in several basketball halls of fame, grew up in Kansas and wound up at the state’s flagship – UK – bumping hips with Dr. James Naismith, who invented the game likely without a clue about what it might become.

Jobe was a talented hoopster, smart as E=mc2, and short. At about 5-feet-8, pro ball was not an option.

So, after graduating from Fisk University, and taking a graduate degree at Tennessee State, there was a short turn coaching high school ball in Alabama. Then, he worked a few moments in Los Angeles in his first wanderlust thrust, joined the Peace Corps in his second and went to teach basketball in Africa for a few years.

“And he loved it,” said Jobe’s widow, Regina, who was at the FSU game along with daughter, Gina Benee Jobe Ishman and grandchildren Caden and Haley. Bryan Jobe, son of Ben and Regina, and his child were unable to make the trip. “He was one of the first coaches. He had to learn and coach all the British sports.”

Upon returning to the United States, Jobe taught for a spell at Rust College in Holly Springs, Miss., before taking his first college head coaching job at Talladega in 1964. Then, there was a brief turn in 1967-68 at Alabama State, in Montgomery, where he met Regina before taking over at South Carolina State from 1968-73.

South Carolina State scored, scored and scored.

Major college freshman were ineligible for varsity competition at the time, and South Carolina — one of the nation’s top programs — played a preseason freshman-only scrimmage against SCS. Felton and the young Gamecocks took a beating. “They blew us out of the gym,” he said. “They ran us out. Transition was their game.”

McGuire soon hired Jobe at South Carolina.

And after four or five years there, Ben split to become the head coach at the University of Denver. Wanderlust again.

“Ben [was] the type of person who gets bored easily. He always challenged himself. Denver came up and he applied. His chances I didn’t think were very good, I think over 300 resumes,” Regina recalled. “He was a restless soul. He liked moving. He didn’t want anybody to ask him to move. He wanted to move first.”

There was another job change in Denver, when after two seasons running the college program Ben joined the staff of the NBA’s Nuggets in 1980-81. That team was coached by Donnie Walsh, another New Yorker who’d coached under McGuire at South Carolina.

That job didn’t last long. Jobe became irked when a Denver front office official – not Walsh – gave him grief for getting into Nuggets superstar David Thompson and trying and help him confront off-court drug issues.

“If you had a problem, and he knew you had a problem, he’d let the front office know the player had a problem,” Regina said. “He will not hold his tongue.”

So, the Jobes drove to Montgomery, where Regina had grown up, to her family.

Cremins called, and Ben took a job at Tech in 1981.

Regina and the kids stayed in Montgomery because, “There were children being killed [in Atlanta]. And we both agreed that we would not take our kids there. Either I would go there on the weekends, or he would come here.”

Multiple young people were murdered in Atlanta from 1979-81 with similar marking characteristics connecting the killings. Ultimately, those deaths would be attributed to Wayne Williams, who in 1982 was convicted for the murders of two adults and sentenced to life in prison without ever being charged for the child murders.

Jobe didn’t stay at Tech for long.

Alabama A&M called, and he took off.

“They came after him, and he said, ‘Bobby I want to be a head coach and have my own team,’” Cremins said. “I said, shoot, go.”

At A&M, the Division II Bulldogs finished first or tied for it three times in the Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Conference and were second once in Jobe’s four years before he lit out again.

The family moved to Baton Rouge, La., and he coached Southern for 10 years to wild success with four NCAA Tournament bids.

Jobe stayed still for a while, even as his teams routinely scored and scored and scored, leading the nation in points three times. Said Regina, “We usually stayed four or five years at a place, but Southern was different because the kids were in school.”

Once the kids were old enough, Jobe took off again. He left the SWAC and went back to the SIAC at Tuskegee. Four seasons were so-so, and he went against his grain, and answered the call to return to Southern.

The Jaguars struggled for two seasons, and he left coaching in 2003.

“Ben always said, ‘You never can go back. Once you leave, however you leave, when you go back it’s never the same,’” Regina said. “When he went back to Southern, he found that to be true.“

Not long after, Walsh called. He was in the front office of the NBA’s New York Knicks, and he wanted to Jobe scout college players around the country. He did, for several years, and his widow said he loved traveling the country and engaging young people.

Even in his 80s, Ben wanted to move.

“That was the philosophy,” Gina Benee said of her father. “That’s in the book he wrote, ‘Staying Ahead of The Posse.’ Part of his thing was not to get bored; go build a program and take on a challenge.”

Jobe and the Jaguars were up to it in 1993, when they met the Jackets in the first round of the NCAA Tournament in the McKale Center in Tucson, Ariz.

Southern averaged more than 93 points per game that season, and won rather easily, 93-78.

“They ran us off the floor,” said Cremins, who spoke at Jobe’s funeral.

The signature win of Ben Jobe’s head coaching career didn’t leave him completely happy.

He told reporters after the game, “If I wouldn’t get fined, or if I could afford to pay the fine, I wouldn’t even talk to you guys. I love you guys, but I’d love you a lot more if you could write about the homeless or poverty on the delta of Mississippi.”

Plus, Ben Jobe remained close to Bobby.

“For my dad, it was so bittersweet for him, because he was playing his long-time friend. He was so humble in his win,” Gina Benee said. “It was nothing that you would ever hear my dad talk about. His only thing was to think about his friend.”