By Thomas Stinson

They knew there would be trouble as soon as the team van topped the hill at Alexander Memorial Coliseum. A crowd that had been fermenting there for hours surged toward the vehicle. It was late March the night Georgia Tech had flown so hard into the face of basketball’s aristocracy and won the ACC Tournament.

Here the student body had come to laud the champions. And now inside the van, the players’ mood turned grim.

“Everybody was jumping on the van, chasing behind us when we got over to the coliseum,” said John Salley. “We’re all inside scared to death. I remember that. They’re jumping on the top. You don’t know if they’re drunk or what.”

Mark Price had sensed the danger and slipped away in another car with his parents. The irony of the moment was lost in the darkened streets. After three years of torment, worrying if success would ever come to the emaciated little program on Techwood Drive, here were Salley and Price, frightened by the arrival of that prosperity. In this van surrounded by yowling students, the circle had come complete.

Or had it?

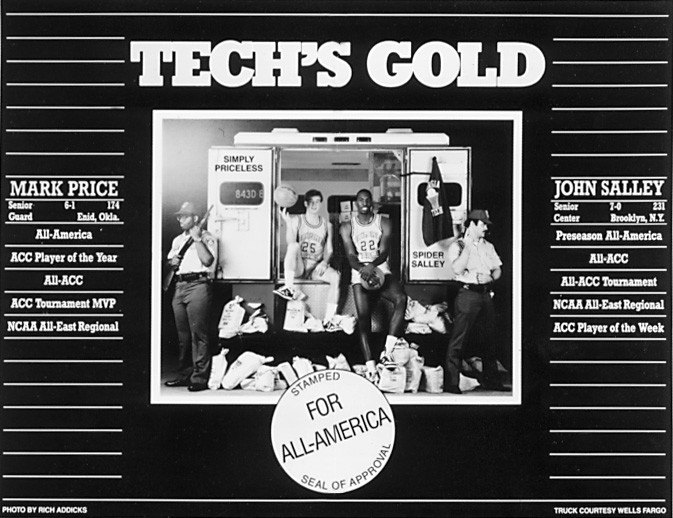

Mark Price and John Salley, the two players who have ridden shotgun during Tech’s return to grace, have maybe one month left as college players. Where before they had wondered if their time would ever come, now they wonder if that time has come too fast. The ACC Tournament this weekend is a silent warning to the two seniors that the dance is almost done.

“There’s only one thing left I want to do,” said Price, who was named to the all-ACC team for the third straight year. “I really think by winning the ACC last year (1985), we’ve really accomplished everything else. Obviously making first-team all-America would be nice. But I’d rather win a national championship.”

From Oklahoma to the Big Apple

If anything that profound came out of Bobby Cremins’ mouth five years ago when he was recruiting Salley out of Brooklyn or Price out of Oklahoma, the Tech coach would have been laughed out of their homes. In his first full year of recruiting, he was looking for a scoring guard and a big man. What he couldn’t know—what college basketball never suspected—was that he’d found the foundation of a national contender.

“I’ve got to give those two the credit for starting the program,” Cremins said. “The way they’ve handled themselves, what they’ve done for me and the program, they are two very, very, very special people.”

Salley, in fact, felt something the same for Price the first time they met in 1982, if for a different reason. He rushed into Price’s room upon arriving at Tech in the middle of the night, woke him up to introduce himself and nearly dropped from shock when a little Caucasian with droopy eyes sat up in his bed. Salley had expected, well, expected something else. Like Michael Jordan maybe.

“This little white dude’s shootin’ it 25 times a game?” said Salley.

“My first two years here, especially the first one when we were having such a tough time, there was never a doubt in my mind that we were going to be good, you know, by the end of my career,” said Price. “I don’t know why I felt that way but I knew we had more players coming in. I don’t know. I guess I’m a positive thinker.”

But if these were the worst of times, in some ways they were also the best. With lessened expectations, Cremins was easier on his freshmen. Tech went 0-7 on the road within the conference and no one flinched. This was the year of the infamous three-point basket in the ACC, the ring just 18 feet away from the basket. For Price, that was a layup.

“I’d just catch the ball,” he said, “and look down to see where the line was. I had a lot of fun my freshman year. ‘Course, I didn’t know what I was doing.”

Price led the league in scoring with 20.3 a game and spawned a defensive strategy heretofore unseen in the ACC, if anywhere else. Late in close games, opposing guards would play Price from behind, forcing him away from the three-point line, giving up the unobstructed 15-footer for its lessened point value. It was all novel for Salley as well. In his first meeting with Ralph Sampson, the Virginia center blocked eight of his shots. Enraged, Salley clipped him on the chin with an elbow on the way up with a hook shot. Sampson shook his head and blocked that one, too.

“We went to the ACC Tournament and beat Maryland,” said Salley. “And we were garbage.”

But then it’s not easy, being garbage.

Evolution of a Point Guard

We didn’t have a Christmas tournament to go to that year so we had two-a-days for two weeks straight,” Salley said. “It was scrimmage and practice. I was in Burger King every day, and it got so I couldn’t get enough sleep. All we did was practice and sleep. Didn’t have any cars, so we’d walk back to the dorms, sit down and it seems just an hour and a half later it was time to go get taped again. It was the most disgusting thing I’ve ever gone through.”

Said Price, “My toughest year was my sophomore year, when I was being transformed into a point guard. There were a lot of frustrations that came with that. When you’ve played a certain way your whole life and all of a sudden you’ve got blinders put on you, it’s a hard thing to have to handle. It was a tough year, but I guess the Lord was looking out for me because I made all-conference and I didn’t even have a good year.”

He ended the season being pulled from an NIT game at Virginia Tech, where he’d scored just 13 points while Tech lost by three. Long before the team had finished showering, he was changed and sitting alone in the bus outside, looking into the night.

Bruce Dalrymple had arrived and then Duane Ferrell. But by then the Salley-Price alliance had come to symbolize Tech basketball. Dissimilar not only in background but manner, close when it counted but distant just the same. As a rule, your urban black master-rappers don’t hang full time with Oklahoman gospel singers.

“Our friendship?” asked Salley. “Our friendship is that we both made the same commitment to come here when no one else would. We both had the same ideas we were going to make something of ourselves, and it has worked.”

“John and I are friends, but we’re two different people,” Price said. “We’ve always liked each other, but when we leave the floor we don’t see each other much. That’s fine with me and that’s fine with him. Sometimes it’s good to get away from your teammates. You spend half your life with them.”

More Than Statistics

As far as player development, Price’s game underwent extensive work with virtually no drop-off in performance. As he was his freshman year, Price remains a sound little guard with ICBM shooting range who has a strong chance to play professionally. Conversely, after seasons fraught with inconsistency, Salley may have just found himself within the last month, even though the NBA types have been raving over him for more than a year.

“John, statistically, is no Mark Price,” said Cremins. Indeed, while both players had their number retired, Price set 10 school records, Salley set one (blocked shots) and tied another (most fouls in a season). “But John has done a lot. He’s recruited these other guys, he’s accepted a lot of stuff I’ve thrown at him, he’s started every game since I’ve been here.

“Offensively, Price has made me look like a great coach because he puts the ball in the basket. But what I really admire about Mark is he could be averaging 30 points for another coach but he’s listened to me and he’s become our leader. I really admire his sacrifice because the little guy likes to shoot.”

They’ve provided a comfort zone these four years for Tech followers who have come to expect that even 23 feet away from the hoop, just one little sloppy pick means a Price basket. Right now, Salley is producing some of the best basketball of his life.

Both Price and Salley have been nominated for the Wooden Award, Tech the only school to have two candidates. And there’s a whole postseason, where the Yellow Jackets were galvanized last year. Possibly, they have nine games left, three in the ACC, six in the NCAA.

But then the coach remembers that with two losses, John Salley and Mark Price will be done at Georgia Tech.

“Yeah, that scares me,” Cremins said. “It scares me to death.”

Reprinted from the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, March 5, 1986.